DALL-E vs. Imagen: How Photorealistic AI Images Can Enhance Products

New developments in the field of AI offer impressive capabilities to generate lifelike images. But how do these work, what are the limitations, and in what products we might see them in the future?

👋 Hey, it’s András here! I write about all things product management: concepts, frameworks, career guidance, and hot takes to help you build better products. Subscribe for each article to be delivered when it’s out!

If someone asked you to create an image of “an astronaut lounging in a tropical resort in space in a photorealistic style”, would you be able to do it? And if so, how much time would it take?

Seconds—at least that’s the promise of some new development in the field of AI.

While we’re very far from the artificial intelligence levels of the Terminator movies, machines and AI models have been steadily developing over the past years. In the last two months, both OpenAI and Google announced a new model of theirs, one that can generate photorealistic images based on text prompts.

Say hello to DALL-E 2 and Imagen!

The technology is early, and the access is very limited, but it has great potential for the future. And as with any advancements, these models also raise a few questions:

What are the limitations of this new piece of technology? What products could take advantage of the generated images? And how could we prevent misuse?

The way it works, differences & limitations

Both AI models work in a similar way: first, they take the user-inputted text and generate a relatively small image (64 x 64 pixels). Then, the image gets processed over and over to enhance it with additional details (“super-resolution diffusion”), resulting in the final image (1024 x 1024 pixels).

Yes, something like those crime series where they reconstruct a face or a number plate out of a blurry security video. But that part in those series remains science fiction, as it’s simply impossible to recreate the real face out of 4 pixels only.

To create a random face that has no connection to the original? Yes, that’d be possible!

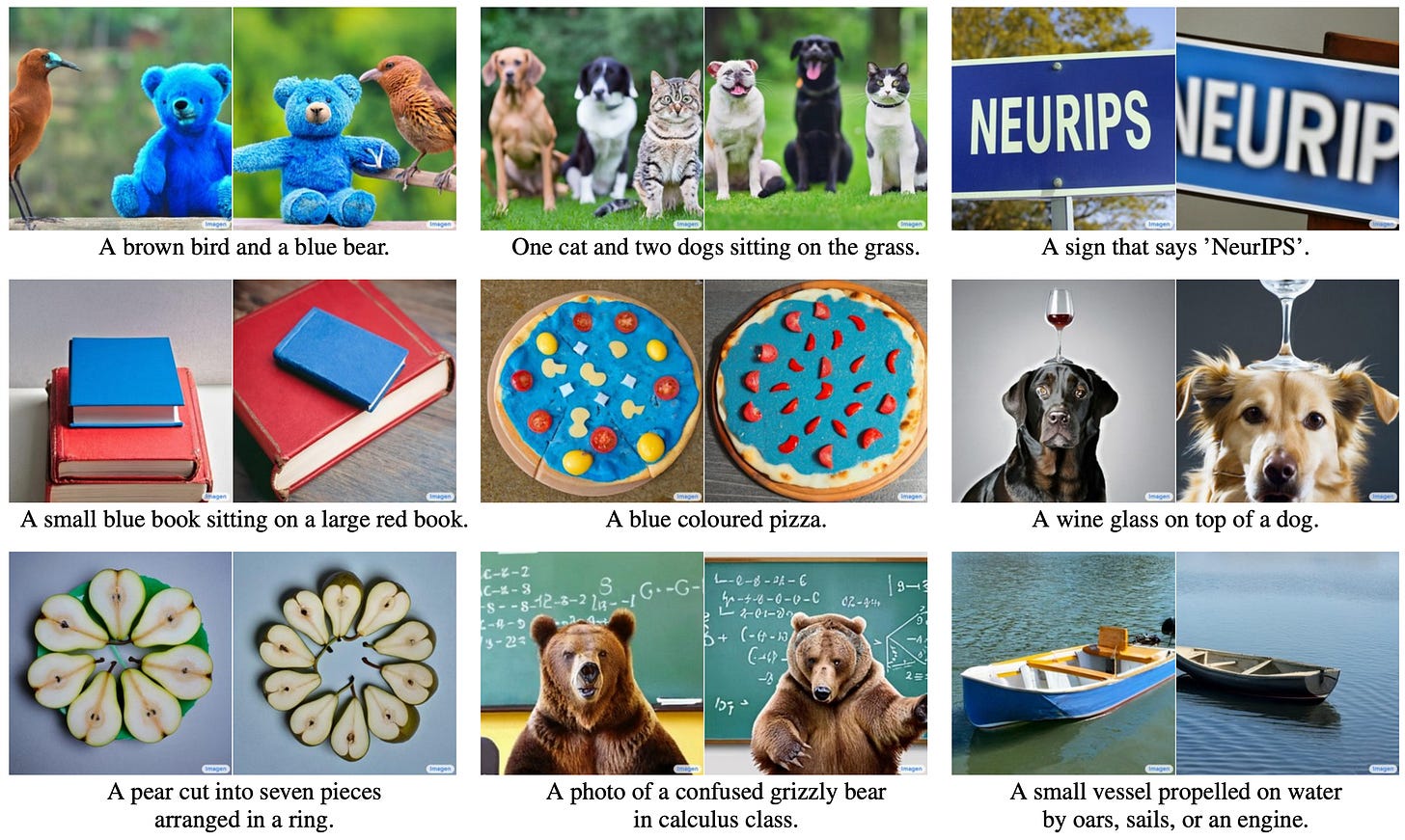

In order to generate the images, both AI models need to correctly recognize the prompted text first and details such as relative word positioning or adjectives.

Do you want to see a “blue apple on top of a red book”? Then these models need to recognize what’s blue and red, what items they’re linked to, and what’s on top of what.

This exercise is not an easy feat, and Google seems to have an advantage here if we’re to believe their research paper. They state that they’re better at recognizing the context between words, and based on the published samples, they’re seemingly better at rendering text.

And while the two solutions are similar in concept, they have slightly different capabilities.

DALL-E 2 is not only capable of generating images from text prompts, but also able to add or remove elements from an image (respecting lightning and shadows), or create different variations inspired by the original picture.

In contrast, Google’s Imagen solution focuses on creating photorealistic images out of the text prompts instead of image manipulation. The company has years of experience in machine language understanding with wide-scale products like Google Assistant, so an advantage here is expected.

Both AI models look promising based on the samples, but it’s also clear that the technology is early—it’s easy to spot blurry parts or abnormal objects on the rendered images.

Productizing the AI models

Today, both of these AI models are primarily available to researchers, hinting that the technology is not yet ready for a wide-scale utilization. Although in the future, we might see a couple of products leveraging the advancements.

In the consumer space, it’s easy to imagine applications using this that are working with user-generated content or managing online identities. A new way to create online avatars, personalizing content in entertainment or gaming, customized animations, or trying to make a living out of generating non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

And regarding the last point, OpenAI clearly thought people would want to use the technology to sell NFTs, as they’ve worded the following part to their content policy:

You may not license, sell, trade, or otherwise transact on these image generations in any form, including through related assets such as NFTs.

On top of the consumer use cases, businesses and creators can also see a huge potential in the new developments. Imagine photo editing tools getting a “prompt to generate image” functionality, or agencies creating even more attention-grabbing creatives for advertising.

Two important factors need to improve before we see these AI models in real products.

Scaling: For this to appear in various applications, the AI model should be able to do many parallel renditions in a given timeframe, and those need to be fast. Users won’t wait minutes or hours in most cases to get the results.

Reliability: Not just increased confidence that the technology will provide the expected results, but that it’ll output images that are safe to use, especially for brands whose audience include minors.

A few open questions that need an answer

As with every new development, these AI models also raise a few important questions.

First, who owns the content rights for the generated images? Technically, users provide the input to the AI model to generate the work, but the AI is doing the heavy lifting. For example, how much difference is needed to recognize a generated image as unique if it was created by tweaking an original artwork?

Second, as explored above, how can we prevent misuse? Or, should the companies behind the models provide safeguards at all to prevent people from generating harmful, illegal, or adult content? If so, what should be the exact rules, and how can providers ensure they’re kept?

Third, our world is full of known brands and people. How should these models respond when users ask them to generate the face of a public figure, a well-known cartoon character, or a widely recognized brand? Would inputting “Michael Jordan drinking Coke while losing a basketball match against Bugs Bunny” work?

These questions will be important to answer before the technology is released to the wider public to take advantage of.

What to expect in the next years

As discussed before, the technology is still relatively new, so it’s likely years away until we see it being utilized in real products. But when we do, we might see different versions of it fine-tuned for specific applications.

One that can draw Disney characters only, one that is limited to painting in Van Gogh’s style, and maybe another one that only creates Garfield comics.

But in most cases, it’ll be a delighter functionality, not a critical one to have.