Two Concepts for Better Product Decisions

You don't need a lot of confidence to change the color of a button, as it's easy to undo if you're wrong. But how do you decide to go ahead with bigger changes?

Great products are not just looking good or working as expected. There is a lot of work and consideration behind the scenes that regular users don’t see in order to create exceptional experiences. One part of this work is all the decisions that lead to the final outcome.

But how do you make good product decisions?

This article is not about product-market fit, prioritization, or the importance of experimentation. Rather than writing about specific exercises to make better products, I would like to talk about some of the “decision how”s.

It’s the combination of two simple concepts: confidence and reversibility.

1. Confidence

Imagine you’re buying ice cream and have a minute to decide on the flavor. Easy. Now, imagine that you’re buying a new car and have the exact same minute to decide on the brand. Not so easy anymore.

Your level of confidence in a situation greatly influences your willingness to make a decision. It sounds easy, but there are two reasons why you’re hesitating: lack of knowledge or fear of consequences.

When developing products, you need to be confident that you’re making the right calls, no matter if you’re launching a new solution or just adding some small enhancements. But the levels of confidence needed for these two things are vastly different.

Launching a new product needs knowledge about the potential users, the competitive landscape, and the market itself — just to name a few. It takes time and resources to get that information and build up high-enough confidence over time that the solution will succeed.

On the other hand, introducing small changes to an online application does not require the same amount of time investment. You probably validate the plan or have users requesting a similar feature, but it’s enough to settle on a lower level of confidence.

When making a product decision, think through how much confidence you would need to go ahead with a proposal. Smaller adjustments usually don’t need a very high confidence level, while breaking changes might.

2. Reversibility

Let’s get back to the previous example. What happens if you end up with an ice cream flavor you don’t like? You might go back to the ice cream shop and choose another seasoning, paying a dollar or two as an extra.

What happens if you buy the worst car in your life? First, you will consider keeping it. Then, you try to get rid of the vehicle at not a too huge loss. After that, you go and buy the correct model for the second try. In the process, you might lose a few hundred dollars.

Reversibility means that some decisions can be easily undone, while others cannot be or don’t worth to be. This is sometimes referred as one or two-way door decisions.

Reversible decisions are like doors that are opening both ways, so they are two-way. If you make a mistake, you can easily walk back on your choice and get back to the drawing board again. On the other hand, irreversible decisions are like one-way doors. Once you make a particular call, you have to live with your choice. It’s either impossible or very costly to revert things how it was before.

Two-way decisions are usually made faster and indicate smaller changes in a product. A/B testing is a prime example. To evolve the experience, you do experimentation. You want to know what works and what doesn’t. While the changes are not groundbreaking, you get into fast learning cycles that help you make better decisions quicker.

Contrarily, one-way decisions require great deliberation and consultation. Introducing new products, choosing a programming language, or refactoring whole applications for performance gains are such choices. In those cases, you need early signs that the plan will be worth it. Otherwise, you risk investing resources into a project without clear evidence.

One of the first steps in making better decisions is that you need to recognize one-way and two-way door decisions. If you find something that seems irreversible, try to find ways to make it reversible.

Using the two concepts together

In a practical sense, confidence and reversibility are not black or white concepts. In every situation, you end up having some from one and a different amount from the other.

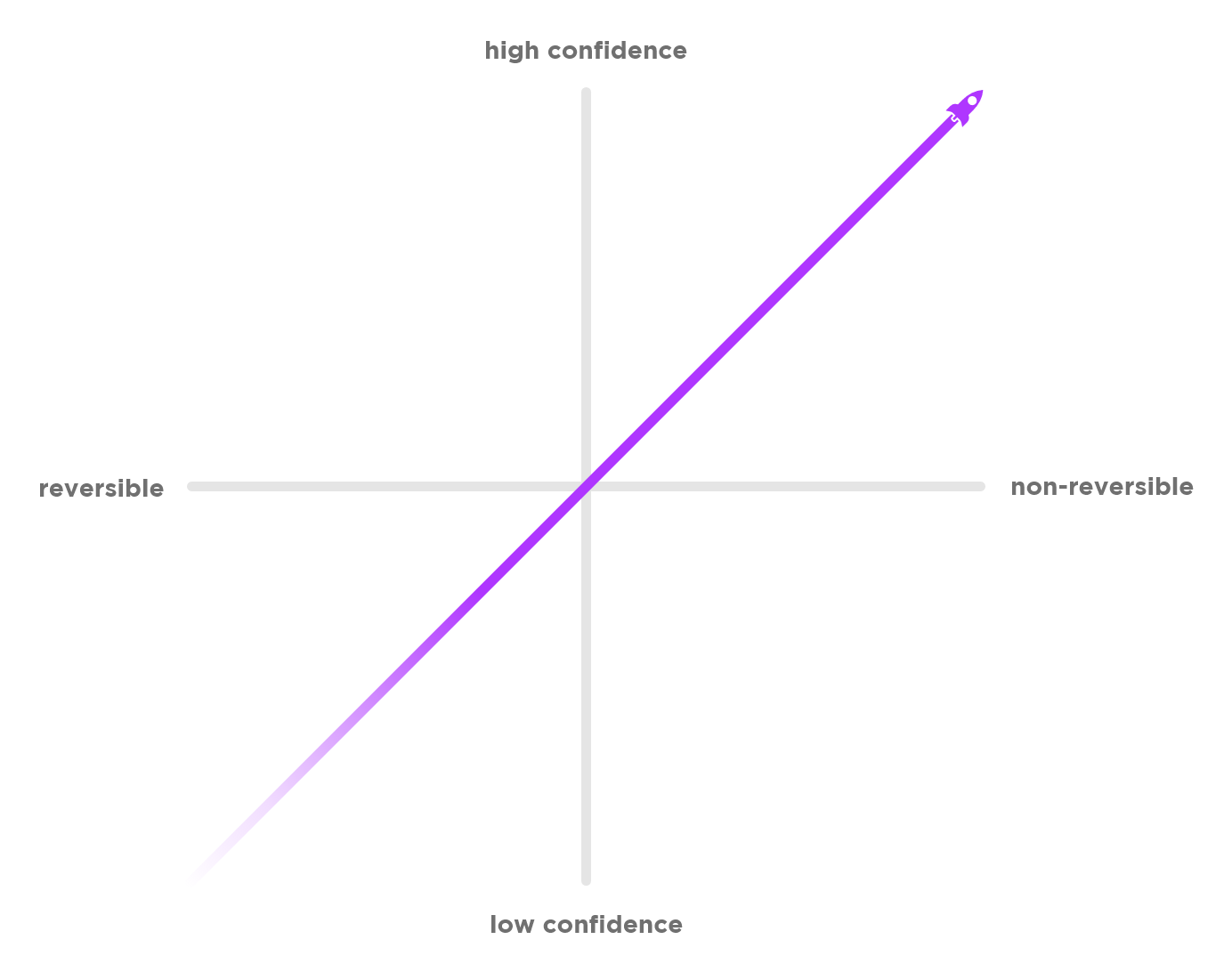

The following matrix illustrates how these two aspects come together. There is a simple rule to keep in mind: the higher the irreversibility of choice is, the higher your confidence should be.

From the chart above, you should avoid the top left and bottom right corners.

On the top left, your confidence is very high in a decision that is likely to be easily reversible. Here, you might waste your time chasing other means of validation when it’s not really required.

On the bottom right, you’re faced with a one-way decision and a shallow confidence level. In this case, you should invest more time in making sure your choice is rock solid before risking investing in something that fails.

And why do I call the chart above “spaceship matrix”?

Because at the very top, with close to no reversibility and very high confidence, you might risk building spaceships. They’re cool, but they also take a lot of effort to build. And the worst part is that you only get to really know if they actually fly at the very end.

If you can, focus on making smaller decisions but more often. Those choices will likely end up being reversible, so even if you make mistakes, you will learn often.